Age and Dementia (they’re not the same thing)

Marsha Henry Goff

We have heard a lot of talk about age and dementia lately. People often refer to age when what they really mean is dementia. Those words refer to two different conditions. Just because your birthdays are rolling around does not mean you will get any of the many types of dementia. In fact, the likelihood is that you will never suffer from dementia.

According to the National Institute of Health, these are the types of dementia:

As we age, it is easy to worry that something is wrong when we forget a name or a word or do something silly like having our glasses on top of our head and looking all over the house for them. About 20 years ago, I made a four-quart batch of potato soup expecting it to last three meals, but I could not find it after the first meal. Normally, I placed it in the refrigerator but I was distracted when cleaning up and had to throw it out when I found it in the lazy Susan cabinet where I kept my Corning cookware.

And I once wrote in my Jest for Grins humor column that, at the age of 15, I went into the kitchen to get a cookie. I took the gum out of my mouth to eat the cookie, then threw the cookie in the trash can and put the gum back in my mouth. Things like that are funny when you are 15, but seem a bit sinister when you are a senior.

The Population Research Bureau (PRB) is a long-term partner of the US Census Bureau that collects and supplies statistics for research and/or academic purposes on the environment, health and structure of populations. According to its research, the proportion of adults ages 70 and older with dementia declined from 13% in 2011 to 10% in 2019.

Only 3% of adults ages 70 to 74 had dementia in 2019, meaning 97% did not. I have not found statistics for people 75 to 84, but PRB says that 22% of people 85 to 89 have dementia (78% do not) as do 33% of people 90 and older (67% do not). But here is what I wonder: the older one gets, the likelihood is that they are taking prescription medicines. I am not a doctor but I have observed how medication can affect a person’s cognitive skills and many medications caution about driving while taking them. Can some people diagnosed with dementia actually be taking too many medications? A word of caution: If you have questions or concerns about your medications, do not stop taking any medicine without first talking with your doctor.

My friend Jane’s mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and was placed by her doctor on the medication Aricept. When her condition became worse, instead of assuming it was the progression of the disease, Jane took her mother to a geriatrician at KU Medical Center who took her off Aricept and much of the medication she was taking and her cognitive skills improved. Jane’s mother was over-medicated.

My husband seriously reacted to an over-the-counter medication so do not assume that a medication is safe just because it is non-prescription. When Ray’s thought processes became loopy and he became highly agitated, it was scary to both of us, I did not know that a nurse had given him samples of 12-hour Mucinex during our 2014 annual physicals and neither of us had read of the following rare neurological and psychiatric side-effects: headache, dizziness, tremor, excitability, irritability, tolerance and dependence (with prolonged pseudoephedrine administration), anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, hallucinations (particularly in children), paranoid delusions and sleep disturbance.

See why it was scary? He didn’t have all of those symptoms, but he had enough of them that we knew something was radically wrong. It was Ray who finally realized what was causing the problem. It took several days for the drug to exit his system and he was fortunate that it was only a matter of days because some psychiatric side-effects can be long-term.

Ray’s reaction was apparently to the coating on the pill that made it extended because he was able to take regular Mucinex. His physician said that some people reacted to the coating ingredients as they would to cocaine. An online search does show that someone using cocaine can have similar neurological and psychiatric reactions. I cannot imagine why anyone would deliberately ingest anything that could cause such scary reactions.

Some types of dementia may have some of those symptoms and I wonder if a doctor who was unfamiliar with Ray would have diagnosed him with dementia. That is exactly why I wonder if some of those 85- to 100-year-olds who are in the 22% or 33% of people those ages who are diagnosed with dementia may instead be having reactions to their medication. It is possible. Again, do not stop taking any medications without consulting your doctor.

I am fortunate that my long-lived forebears were excellent aging role models. Read the tombstones in the Henry cemetery plot and the ages are 91, 95, 97, 98, 104 and in the Shellhammer plot, 87, 92, 94, 95 … you get the picture. Not one of them had dementia.

My Grandfather Jake Shellhammer enjoyed grafting different fruits onto the same tree, A school teacher, he taught me cursive writing, making me use a big nail to form the letters so I wouldn’t waste ink. He died the day after his 92nd birthday, but not before he walked many blocks down to the post office of his small Oklahoma town to retrieve his mail and return home where he lay down for a nap before lunch and, as the preacher at his funeral said, “woke up with the angels.”

I had my Grandmother Ruth Henry the longest of all my grandparents. I was 41 when she died a few months before her 92nd birthday. Grams was as tough as nails. I snapped the accompanying picture of her on her 81st birthday as she demonstrated how to use the exercise wheel I had purchased for myself. I recently had a story about her titled “She did it herself” published in Mothers and Daughters, a Chicken Soup for the Soul book. Look for the notice on this page to see how you can win a free book and read about Grams’ “never grow old” exploits.

If you are someone who worries about getting dementia as you and/or a loved one grow older, I hope this article will relieve your mind about that concern. The odds that you will never be diagnosed with dementia are certainly in your favor.

According to the National Institute of Health, these are the types of dementia:

- Alzheimer’s disease, the most common dementia diagnosis among older adults. It is caused by changes in the brain, including abnormal buildups of proteins known as amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

- Frontotemporal dementia, a rare form of dementia that tends to occur in people younger than 60. It is associated with abnormal amounts or forms of the proteins tau and TDP-43.

- Lewy body dementia, a form of dementia caused by abnormal deposits of the protein alpha-synuclein, called Lewy bodies.

- Vascular dementia, a form of dementia caused by conditions that damage blood vessels in the brain or interrupt the flow of blood and oxygen to the brain.

- Mixed dementia, a combination of two or more types of dementia. For example, through autopsy studies involving older adults who had dementia, researchers have identified that many people had a combination of brain changes associated with different forms of dementia.

As we age, it is easy to worry that something is wrong when we forget a name or a word or do something silly like having our glasses on top of our head and looking all over the house for them. About 20 years ago, I made a four-quart batch of potato soup expecting it to last three meals, but I could not find it after the first meal. Normally, I placed it in the refrigerator but I was distracted when cleaning up and had to throw it out when I found it in the lazy Susan cabinet where I kept my Corning cookware.

And I once wrote in my Jest for Grins humor column that, at the age of 15, I went into the kitchen to get a cookie. I took the gum out of my mouth to eat the cookie, then threw the cookie in the trash can and put the gum back in my mouth. Things like that are funny when you are 15, but seem a bit sinister when you are a senior.

The Population Research Bureau (PRB) is a long-term partner of the US Census Bureau that collects and supplies statistics for research and/or academic purposes on the environment, health and structure of populations. According to its research, the proportion of adults ages 70 and older with dementia declined from 13% in 2011 to 10% in 2019.

Only 3% of adults ages 70 to 74 had dementia in 2019, meaning 97% did not. I have not found statistics for people 75 to 84, but PRB says that 22% of people 85 to 89 have dementia (78% do not) as do 33% of people 90 and older (67% do not). But here is what I wonder: the older one gets, the likelihood is that they are taking prescription medicines. I am not a doctor but I have observed how medication can affect a person’s cognitive skills and many medications caution about driving while taking them. Can some people diagnosed with dementia actually be taking too many medications? A word of caution: If you have questions or concerns about your medications, do not stop taking any medicine without first talking with your doctor.

My friend Jane’s mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and was placed by her doctor on the medication Aricept. When her condition became worse, instead of assuming it was the progression of the disease, Jane took her mother to a geriatrician at KU Medical Center who took her off Aricept and much of the medication she was taking and her cognitive skills improved. Jane’s mother was over-medicated.

My husband seriously reacted to an over-the-counter medication so do not assume that a medication is safe just because it is non-prescription. When Ray’s thought processes became loopy and he became highly agitated, it was scary to both of us, I did not know that a nurse had given him samples of 12-hour Mucinex during our 2014 annual physicals and neither of us had read of the following rare neurological and psychiatric side-effects: headache, dizziness, tremor, excitability, irritability, tolerance and dependence (with prolonged pseudoephedrine administration), anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, hallucinations (particularly in children), paranoid delusions and sleep disturbance.

See why it was scary? He didn’t have all of those symptoms, but he had enough of them that we knew something was radically wrong. It was Ray who finally realized what was causing the problem. It took several days for the drug to exit his system and he was fortunate that it was only a matter of days because some psychiatric side-effects can be long-term.

Ray’s reaction was apparently to the coating on the pill that made it extended because he was able to take regular Mucinex. His physician said that some people reacted to the coating ingredients as they would to cocaine. An online search does show that someone using cocaine can have similar neurological and psychiatric reactions. I cannot imagine why anyone would deliberately ingest anything that could cause such scary reactions.

Some types of dementia may have some of those symptoms and I wonder if a doctor who was unfamiliar with Ray would have diagnosed him with dementia. That is exactly why I wonder if some of those 85- to 100-year-olds who are in the 22% or 33% of people those ages who are diagnosed with dementia may instead be having reactions to their medication. It is possible. Again, do not stop taking any medications without consulting your doctor.

I am fortunate that my long-lived forebears were excellent aging role models. Read the tombstones in the Henry cemetery plot and the ages are 91, 95, 97, 98, 104 and in the Shellhammer plot, 87, 92, 94, 95 … you get the picture. Not one of them had dementia.

My Grandfather Jake Shellhammer enjoyed grafting different fruits onto the same tree, A school teacher, he taught me cursive writing, making me use a big nail to form the letters so I wouldn’t waste ink. He died the day after his 92nd birthday, but not before he walked many blocks down to the post office of his small Oklahoma town to retrieve his mail and return home where he lay down for a nap before lunch and, as the preacher at his funeral said, “woke up with the angels.”

I had my Grandmother Ruth Henry the longest of all my grandparents. I was 41 when she died a few months before her 92nd birthday. Grams was as tough as nails. I snapped the accompanying picture of her on her 81st birthday as she demonstrated how to use the exercise wheel I had purchased for myself. I recently had a story about her titled “She did it herself” published in Mothers and Daughters, a Chicken Soup for the Soul book. Look for the notice on this page to see how you can win a free book and read about Grams’ “never grow old” exploits.

If you are someone who worries about getting dementia as you and/or a loved one grow older, I hope this article will relieve your mind about that concern. The odds that you will never be diagnosed with dementia are certainly in your favor.

My article about my brother-in-law Steve Julian's posthumous journey into space

recently appeared in Kaw Valley Senior Monthly.

Steve Julian: Posthumous Astronaut

Marsha Henry Goff

Marsha Henry Goff

When SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket was launched from Kennedy Space Center on May 22, 2012, its Dragon capsule carried supplies for the International Space Station, the first non-government vehicle to dock there. However, for many of the people who crowded Florida’s Jetty Park to watch the night launch, the second stage of the rocket carried a secondary but extremely precious cargo: vials containing the ashes of their loved ones which, with a successful launch, may orbit the earth for several years. One of those vials contained the cremains of Steven Mark Julian, my brother-in-law.

On October 4, 1957, a day after his 7th birthday, Steve was bitten by the space bug when Russia launched Sputnik. For the rest of his life, he was fascinated by space and continued to arrange his work schedule so he could watch televised launches long after they became routine for most Americans. Because he was watching the only network to televise live the launch of Challenger on January 28, 1986, he knew about and mourned the tragedy before some media outlets interrupted their scheduled programming with news that the rocket carrying the shuttle had exploded. Although his childhood dreams of becoming an astronaut were never realized, Steve’s life was full. During his high school and college years, he worked in a grocery store, advancing after graduation to night manager. He married the love of his life, my sister Vicki, and fathered two sons, Chris and Ryan. Our family was proud of Steve as he became an insurance agent and then a life insurance consultant assisting agents working for a brokerage company. After Steve’s death, his company established a highly coveted award that is given annually in his name. When Steve was diagnosed with a rare cancer in 2004, it was not long after extensive surgery before he returned to work and resumed his rigorous exercise schedule. He embraced Relay for Life and proudly walked the survivor’s lap. A medicine held the cancer in check for a year, but failed when the cancer mutated. As Steve and Vicki traveled from Houston to Chicago, chasing an elusive cure, it became obvious to Steve and all of us who loved him that he was in a battle he could not win. In palliative care, Steve spoke to Vicki of cremation and she immediately recalled their earlier conversation |

when the ashes of Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, were sent into orbit in 1997. An Internet search located Celestis, the company responsible for launching into space Roddenberry, Timothy Leary and others, both famous and not. Vicki promised Steve that he posthumously would become the astronaut he always wished to be.

After several launch delays resulting in canceled and rescheduled flights and hotel reservations, Vicki, her sons, daughter-in-law and my husband Ray and I flew to Florida for the launch which was expected to occur on May 19. Out on the jetty in the middle of the night, we watched across a wide expanse of ocean for the launch of the rocket which also carried the ashes of L. Gordon Cooper, one of America’s original Mercury 7 astronauts, and James Doohan, better known as Scotty on Star Trek. Excitement grew as we saw the light on the horizon grow brighter, knowing it resulted from the engines firing on the rocket. The countdown reached "Liftoff" but the rocket failed to rise. High pressure in one of the rocket’s engines caused the computer to shut down all engines and abort the launch. Ray and I could not rearrange our schedules for a second launch attempt planned for May 22, but Vicki was determined to witness the fulfillment of her promise to Steve. While I watched the 3:44 a.m. launch on NASA’s website from our home in Lawrence, Vicki and her children were standing on the jetty. As the rocket carrying the ashes of 320 people, representing 18 countries, rose in the dark sky, Vicki, her promise kept, threw up her arm in triumph and shouted a fitting tribute for her native Kansan husband: "Ad astra, Steve!" Note: The second stage of the rocket carrying the ashes of Steve and many other souls orbited the Earth 576 times, about once every 90 minutes, before reentering Earth's atmosphere over the South China Sea at 10:22 p.m. CDT on June 26. Those interested in learning more about space memorials may do so by clicking HERE.

|

The following article appeared in the Fall 2011 issue of Amazing Aging

The unlikely friendship that helped produce

an Oscar-nominated film

Marsha Henry Goff

an Oscar-nominated film

Marsha Henry Goff

|

The long-ago friendship that developed between Leo Beuerman, a crippled dwarf, and Catherine Weinaug, a KU professor’s wife, was surprising to everyone except Catherine’s son, then a boy but now Douglas County Administrator Craig Weinaug. He says he was never surprised at anything his mother did. She had a strong, energetic faith and never shied away from recruiting others to help her move mountains.

Leo was born on January 6, 1902. By age 10 he began to lose his hearing and by 28 he was deaf. At maturity, he stood 3 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 60 pounds. He invented devices — including a mini-elevator that helped him up and down the steps at his rural farm house near Lakeview — where he lived with his brother and sister. With the help of his nephew, Leo adapted an ancient tractor so he could drive to town and back, carrying the little cart from which he conducted his watch repair business and sold pencils and other items on the sidewalks of downtown Lawrence. Occasionally, he would stay in town all night, sleeping in his cart. One night as he was sleeping, he was pulled from his cart and brutally beaten and robbed. He suffered head cuts and other injuries and was hospitalized. When tender-hearted Catherine read of the attack, she sent flowers to Leo at the hospital, but felt she needed to do more. One day, learning he had been dismissed from the hospital, she followed vague directions given to her by a store clerk to find Leo’s home and visit with him. She was appalled that Leo transported himself about the two-room house on a small wheeled platform and slept leaning against a wooden orange crate. She conversed with him by writing notes on the pad he pressed into her hands. He was thrilled to have company and asked her, “Will you come again? Will you be my friend?” “Our friendship is just beginning,” Catherine answered and meant it. She enlisted help from her husband, Charles, and sons, Carl and Craig, as well as members of a Sunday School class of university students she taught. One Sunday, the Weinaugs took Leo to church where he sat between two students who wrote condensed versions of the pastor’s sermon for Leo. Then he went to the Weinaugs’ home for dinner. He had his first tub bath there. Charles lifted Leo into the tub and left him splashing with glee, while Catherine washed and dried his clothes. “They were almost dry before Leo called |

Charles to help him out of the tub,” Catherine said. “I was beginning to fear he had drowned!”

Leo emerged from his long soak with a big smile on his face and, according to Catherine “left enough dirt in the tub to plant flowers.” He ate dinner seated on three encyclopedias. And when he spent the night, sleeping upright while resting his back against an overstuffed chair instead of his orange crate, his earsplitting snores kept the Weinaugs awake and evoked howls from the family’s dog. Leo became a frequent visitor at the Weinaug home and one day Catherine mentioned to her neighbor, Russ Mosser, who was part-owner of Centron Films in Lawrence, that Leo’s story might make a good movie. She furnished Mosser with Leo’s autobiography, which she had encouraged him to write, and photos of Leo. Trudy Travis, a gifted writer who recently died at age 90, was assigned to write a script. She followed Leo, watching him struggle with chains to lower and raise his cart onto his tractor and seeing him interact with his customers, most of whom were children. “Leo Beuerman,” a 14-minute short documentary, was nominated for an Oscar in 1969. The film is still available on DVD and is often used as a motivational tool by businesses. Leo was totally blind during the last years of his life and friends communicated with him by writing on his back. He lived in a nursing home and helped support himself by making leather key chains and bead necklaces which were sold in local stores. A bronze plaque, sculpted by artist Jim Patti, sits in the sidewalk at the northeast corner of 8th and Massachusetts where Leo frequently sat in his cart. The wording on the plaque was objected to by some who believed the words represented a negative stereotypical view of handicapped persons. Leo’s friends argued that there was no shame in any form of honest labor and said the words were simply Leo’s way of identifying himself. The plaque features an image of Leo in his cart along with his words reproduced in his own handwriting: Remember me — I‘m the little man gone blind. I used to sell pencils on the street corner. Both Leo and Catherine are gone now, but neither will be forgotten by those who knew them and the story of their unlikely friendship. |

The following article appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Amazing Aging.

Jack Wright IS The Sage of Emporia

Marsha Henry Goff

Marsha Henry Goff

Korean War veteran John Studdard revisits Korea

Marsha Henry Goff

Marsha Henry Goff

Rishi Sharma: Appreciating World War II veterans

and documenting their service

Marsha Henry Goff

and documenting their service

Marsha Henry Goff

|

Rishi Sharma is a young man on a mission. The 19-year-old California native formed a non-profit — Heroes of the Second World War — before he graduated from high school and has spent the last ten months traveling throughout the United States interviewing World War II veterans. His quest to interview at least one veteran each day (to date he has interviewed more than 300) is a magnificent obsession and he is passionate about it: “We have a responsibility to document their experiences so that such a devastating war will never happen again and so that those brave men did not die in vain.”

For those who think his interest in World War II veterans is unusual, he explains: “How can you not be interested in a war that killed 70 million people and the veterans who fought it 75 years ago and literally saved the world? If a Civil War veteran suddenly came back to life from the grave, all the world’s media would be hounding him begging for an interview using the nicest equipment and the fanciest cameras. What boggles my mind is that we have this opportunity with the WWII veterans! We should not wait until there is only one left to acknowledge their sacrifices and to document them.” He has put 29,048 miles on his 2014 Honda Civic driving from coast to coast, north to south. His rear window and back |

side windows are decorated with perforated window decals stating his mission. He says it was the best money he has spent because it also provides him with privacy while he sleeps in the back seat. He operates on a tight budget and declares, “I’m not going to waste money on nightly room rent. I have three blankets and I am a lot better off than those who slept in foxholes, don’t you think?”

Sharma has interviewed one Medal of Honor recipient and nine veterans 100 or more years old. When he reads an obituary of a World War II veteran he did not have the chance to interview, he calls the family to express his condolences and his thanks for the veteran’s service. He presents each veteran he interviews with a video of the interview. You may read more about him on his website — http://www.heroesofthesecondworldwar.org/ — and also view many of the veterans he has interviewed. He knows it is unlikely that he will be able to interview every surviving World War II veteran, so he provides a list of questions and encourages visitors to his website to do their own interviews. If you are a World War II veteran or know of one who would like to be interviewed, please email Rishi Sharma at [email protected] or call him at 818-510-2892. |

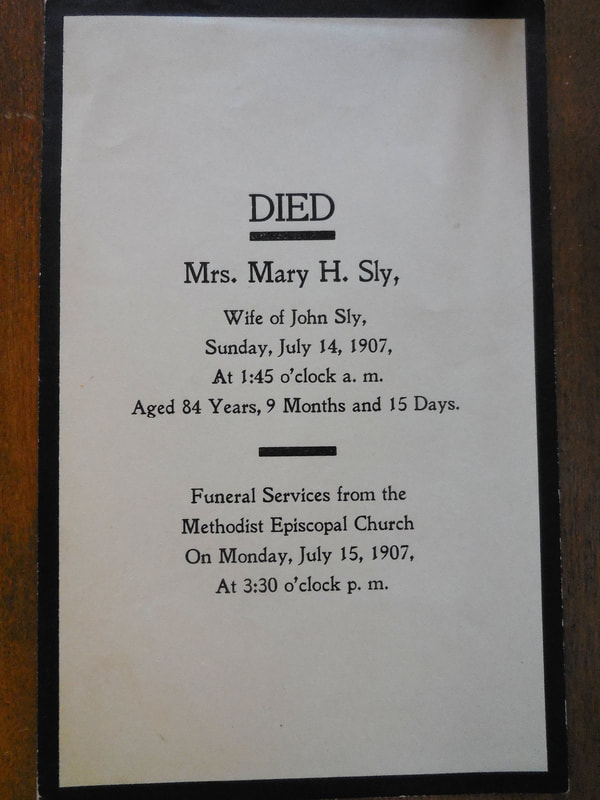

The Life and Times of Mary Hammond Sly

Mary Hammond Sly, my paternal great-great-grandmother, was born on September 29, 1822, near Buffalo, New York. Her father, Benoni G. Hammond, a farmer and teacher, ensured that all thirteen of his children — girls as well as boys — received a proper formal education. Mary Sly graduated from Miss Willard’s Female Seminary in Troy, New York and became a teacher. She taught in New York state for ten years, earning from eight to fifteen dollars a month, until her marriage.

She abandoned spinsterhood in 1850 to marry John Sly, a farmer and abolitionist four years her junior, from Erie County, New York. The Slys farmed in Erie County for five years, then moved to Delaware County, Iowa. In the spring of 1857, they packed all their belongings and their young children, Cornelia and Philo, into an ox-drawn covered wagon and headed west to Kansas Territory where they sought land and breathing space.

In later life, Mary Sly — always politically active — became involved with Woman Suffrage and Populism. But throughout her long life, without neglecting family responsibilities and church and political activities, Mary found time to draw and paint and was diligent in keeping a written record of her thoughts and reactions to the history occurring around her. The words of Mary Sly, existing today in her letters and journal (the only one to survive my great-aunt’s deliberate fiery destruction), relate her character and give us an accurate history of the time.

John and Mary Sly, Nemaha County’s second and third settlers, established a home on Turkey Creek, near the present town of Seneca. During the half-century they lived there, they endured illness, deaths of loved ones, two wars — one close at hand and one distant — and political upheaval.

Wagon trains usually started the trek westward in the spring to avoid the intense cold and bad weather of fall and winter. The trip was especially difficult for Mary for a reason apparent in a letter dated November 22, 1857, which she wrote to her sister Elizabeth back East after the Slys were settled in Kansas. The family would have delayed the journey, she wrote, had she realized she had “started to Boston,” a pioneer’s polite euphemism for pregnancy.

You asked me to write more particularly concerning our journey. I was brief at that time on purpose, and, now shall be obliged to be, for want of time. However you shall have a short history of myself and if it goes to Washington through miscarriage so be it. Well then I did not dream I had “started to Boston” when we made calculations on coming to Kansas or we should not have come this year, but I was three months and over on the route and of course nothing was enjoyed by me. I felt sometimes as if I was going to my long home.

Cornelia and Philo were both very sick part of the time. We camped in our wagon mostly rain or shine, but had some good company the last three weeks. Were over five weeks coming. I have not to add that my lot was case in a goodly place and among good Christian people, and although I have suffered for the want of help to do my work, the neighbors have done all in their power.

An unpleasant initiation to the prairie were cases of malaria (ague) which pioneers often contracted when first out West. While suffering from malaria, Mary Sly gave birth to her third child, a task by no means easy while in good health.

We have all every one had the ague and fever and all down at once but Augustus, he waited till John was getting so that he

could make out to milk if the cow came up of her own accord. My ague came on every other day about 6 o’clock and sometimes I could help about the dinner and again not. I had the fever enough to burn me up almost.

Had it broke with calomel and quinine firstly but came down with it twice later and then employed a botanical Physician, who lives four miles from us in Nebraska, he gave 16 pills to be taken in 8 hours and I have not had but one shake since and that was the next day after my little Catharine Elizabeth was born. A good old lady was obliged to officiate as M.D. as the doctor had just gone, thinking I could wait until in the night. (I was glad he left though.) We could not get but two women and neither of them has a child in the world or ever had, others soon came but too late.

On September 17, 1858, Cornelia, Mary Sly’s oldest child, died of an undetermined ailment. Her death broke my great-great-grandmother’s heart.

Little did I think when I wrote you last that I should so soon have to take my pen again to communicate the sad tidings I do at this time. Yes, my dear Sister, your little favorite is no more. Cornelia, my own sweet darling Cornelia, is I have no doubt praising God in Heaven. She was taken last Thursday, Sept. 16, and died at sunrise the next morning.

She went into a fit about two o’clock and never came to, so as to sense anything to all appearances . . . . But Oh Elizabeth, the look, the last sad parting look she gave me, how can I describe it? I cannot, no I cannot. When I think of it I can scarcely keep from bursting right out crying.

Years later, Mary Sly still wrote of Cornelia in her journal, always with pitiful backward glances. A long poem entitled “Cornelia” — the last stanza of which follows — is especially heartrending.

To God I’ll go with every care,

And humbly seek in earnest prayer

For grace, that we may meet thee there,

Cornelia.

Cornelia Maria Sly departed this life September 17, 1858, aged 6 years nearly. Had Cornelia lived, to-day would have been her 25th birthday.

Without formal declaration, the American Civil War began well before 1861. The war was actually being fought in the legislative branch of national government as early as 1858. One of the main issues at hand was whether Kansas would be a slave or free state. According to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, introduced by Stephen A. Douglas, the residents of Kansas would determine by popular vote whether Kansas would be a pro- or anti-slavery state.

However, in late 1857, pro-slavers submitted the Lecompton Constitution to the state legislature, recommending that Kansas be admitted as a slave state, in repudiation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as well as the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Acting Kansas Governor Frederick P. Stanton put the Lecompton Constitution to a popular vote and the Constitution was soundly defeated on January 4, 1858.

In response, Southern extremists in Congress, backed by President Buchanan, passed the English Bill on the 4th day of May, 1858, which stated that if Kansas was voted a free territory, Kansas residents would lose four million acres of public land grants (i.e., the homesteaders in these areas would have to buy their land) and Kansas would not be declared a state until it had a population of over 90,000.

Understandably, Kansas residents were upset, and Mary Sly exemplifies their feelings in a letter to Elizabeth dated May 8, 1858:

Everything seems to go off right since the rejection of the Lecompton Constitution, except for the fiendish revenge manifested by Buchanan’s late proclamation to sell all the surveyed lands in the territory. The people are forming mob laws for their protection — in some places, not here. James Buchanan, unless he repents, will die an unenviable death, unwept, unmourned, and perhaps unhung.

By December, 1861, the Civil War on the frontier was booming. The Kansas pioneers were themselves victims of war, being caught between the anti-slavery Jayhawkers and the pro-slavery forces. Though on opposite sides, these two groups used the same tactics of terror. In the following letter, Mary Sly describes a run of bad luck and then becomes philosophical about her troubles.

. . . Don’t we have the luck? I do not mind if we can keep our health, and the worse than rebels will leave us alone. The Jayhawkers are all around and we are expecting trouble from them as we have been threatened. I have a poor opinion of them, let them be on which side soever.

At this time, settlers in Kansas were fearful of a large scale attack from Missouri, as the pioneers would be defenseless against the ruffians who despised them. Again in the letter of December 8, 1861, Mary Sly characterizes the settlers’ fears.

We understand that North Missouri is all in rebellion again. We are afraid that as soon as the river freezes over they will step across into Kansas and make all the destruction possible. They hold such a deadly hatred to Kansas.

The huge-scale attack from Missouri did come, but not until 1864, when General Sterling Price and his rebels stabbed into Kansas. In another letter to Elizabeth, dated October 17, 1864, Mary Sly describes the situation.

At present the railroads are all in rebel hands in Missouri, or nearly so, Price in connection with others are playing Smash there . . . Every able bodied man is called off after Price. The present hour for Kansas is a critical one indeed. Indians on the south and west, and rebels on the east and both trying to do her all the injury they can, still I hope she will escape a general extermination.

When the Civil War ended, Mary Sly was in her early forties. Her liberal upbringing, coupled with the physical and economic hardships she endured on the frontier had served to forge her into an iron-hard individualist. Three decades later, Mary Sly used her journal to report with great candor on the social, political and personal events which affected her life in the 1890s.

One of the more serious aspects of life on the prairie was illness and its treatment. Mary Sly reports at length on medical topics, probably due to the fact that four of her eight brothers were doctors, all of whom lost their lives in the Civil War. Her remaining four brothers were dentists.

An acquaintance of Mary Sly, Emma Smith Williams, had breast cancer and was desperate to be healed of it. In April, 1898, Mary Sly wrote in her journal:

She that was Emma Smith is down from Beaty [Nebraska] to consult the doctors about a cancer on her left breast.

Evidently, Mrs. Williams’ prognosis was grim, for less than a week later, she desperately turned to a frontier healer, a charlatan of the type that sold alcohol-based cure-alls to those who hoped for better health. In a journal entry on April 10, 1898, Mary Sly confided her opinion of such “healers.”

Ruth [Mary Sly’s daughter] went with Emma Smith to Kansas City to see Carson the Magnetic Healer, but to no purpose. He is a humbug. Emma went home Thursday. I think the cancer incurable.

Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Williams, still seeking a cure, sought help from a cancer specialist. A July 23, 1898 entry states:

Ruth has just gone to the depot with Emma Williams who has been three months to Wichita doctoring for cancer with Dr. M. S. Rochelle, specialist.

At some point in her treatment, Mrs. Williams had what was then considered very radical and experimental surgery, a mastectomy. Science marches on in the Nineteenth Century, as noted on February 21, 1899.

Mrs. Emma Williams called as she is moving to Oklahoma. She showed me where her cancer was taken off, the left breast all gone.

Perhaps the pioneers’ greatest fear was that of an epidemic, as doctors were scarce and inoculations were rare or for some diseases uninvented. An epidemic of typhoid, smallpox, or diphtheria could strike with devastating results. In her journal, Mary chronicles one of the local smallpox scares.

Feb. 21, 1899. Smallpox in town. Dr. Troughton’s son.

Feb. 22, 1899. Dr. Troughton’s house is quarantined and he is like a caged lyon [sic]. Geo Williams’ folks have left their fine house for a time until the smallpox question is better understood.

Feb. 24, 1899. The authorities have built a Pest House and last night removed young Troughton to it.

Feb. 26, 1899. Conference [Methodist Church] is moved from Seneca on account of smallpox.

March 1, 1899. J. B. [Moriarty, husband of Mary Sly’s daughter Ruth] has just drove up with his new mule team. Their children vaccinated.

March 3, 1899. Young Troughton is still a smallpox patient. He is the only one that has it in town as yet.

March 4, 1899. Hear nothing from the “pest” House, nor of any additional cases. Hope no more have it. Old Mrs. Hale is

quarantined.

March 17, 1899. Mrs. Troughton’s sister in the Pest House, down with smallpox.

The entry on March 17th was the last one pertaining to the smallpox scare. Fortunately, the disease was confined to only a few people, including the local doctor’s son and sister-in-law.

The women’s liberation movement is not a recent one. Mary Sly, in her seventh decade, was extremely involved in the movement and her relatives knew it. On April 11, 1894, she noted in her journal that her brother had sent her an item of mutual interest.

W. W. Hammond sent me a Boston paper in which is a fragment of the welcoming speech to the Equal Suffrage Convention held in Boston last week. I am glad to learn he favors Woman Suffrage.

Mary Sly’s thorough involvement in the Suffrage movement occasionally caused friction with others who were less enthusiastic about it. Once such case occurred after Mary recorded that a church member came to her door on October 31, 1894,

soliciting a chicken pie towards feeding the people on election day,

Nov. 6th.

Before the election, however, a conflict developed between the preacher of the church and Mrs. Sly, about which she says:

If our preacher is too conscientious to vote for Woman Suffrage, the

church may furnish its own chicken pie.

In the 1890s, the United States suffered one of its worst depressions ever. It seemed that nothing could bring the country out of this intolerable slump. Vagabonds were omnipresent, especially in the Midwest, as Mary Sly testifies on May 26, 1894:

Seneca is down on the tramps.

Again, on July 13, 1895, she writes:

Just fed another tramp. The country is full of them. Grover [Cleveland] will get to his end after a while.

And a year later, she is still beset by beggars:

Decoration Day. A tramp to feed calls.

In a time of such poverty, one often becomes quite disillusioned with the whole political system, and Mrs. Sly is no exception. Her disgust is apparent in a November 3, 1894 entry:

Tonight a Democrat speaks at the Hall and the Suffragists at the Court House. They are all such liars I do not want to go.

The disillusionment of many agrarians like Mary Sly led to the formation of a strong new party, the Populists. Those in the Populist Party felt that the depression of the 1890s was due to the fact that the gold standard kept money in the hands of few, and when the gold supply became ever scarcer in the United States, these “goldbugs” would prosper while others starved.

Leading the Populists was a Nebraska gentleman named William Jennings Bryan who said at a speech in Chicago in 1896:

There are two ideas in government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up through every class and rest upon us.

Thus, the Populists wanted a silver and gold standard to place more money in the hands of the less prosperous, namely the farmers.

On November 6, 1896, the Populists’ presidential candidate, W. J. Bryan (a Democrat), squared off against the Republican “goldbug” William McKinley. As did many other farmers, the Slys threw their support to Bryan. The Populists’ dreams were not to be fulfilled in 1896, however, because as Mary reports in her journal on November 11,

Election has resulted in the defeat of Bryan the Free Coinage Candidate, of both gold and silver at 16 to 1, that is 16 oz of

silver = in value 1 oz of gold. McKinley carried 23 states, Bryan 21. Delaware and Kentucky doubtful yet.

Mary Sly’s hopes for free coinage did not end with McKinley’s election, because in January of 1897, she writes:

The year comes in “like a lamb.” I hope it may prove a peaceful and happy year to us nationally. McKinley will soon occupy the presidential chair and if Congress will give the people more money, there will no doubt be greater prosperity.

Without doubt, McKinley’s victory over Bryan upset Mrs. Sly a great deal for she notes on March 4, 1897 that:

Wm McKinley inaugurated to-day. A dull, gloomy day in keeping with the times.

In the late Nineteenth Century, as now, officials in the church felt no trepidation about expressing their political ideas from the pulpit. In 1897, a visiting official from the Methodist Church gave a lecture which greatly angered Mary.

McKabe lectured here the 13th. He is a “gold bug.” I have no use for such bishops!

Meanwhile, Bryan, the free coinage advocate, was still very popular, as Mary tells us on October 4, 1897:

Received and answered Brother William’s invitation to come and hear Bryan speak in Kansas City. Our health will not permit us to go.

She adds on October 7th that,

Bryan’s speech was successful. 15,000 paid $.25.

Mr. Bryan was obviously to remain in the limelight.

In late January, 1898, the U.S. warship Maine was sent to Havana, Cuba, to protect U.S. interests. Only two weeks later, on February 15, 1898, the ship blew up under mysterious circumstances, resulting in the deaths of over 250 American sailors. Mary Sly noted the major event and the controversy surrounding it on March 14th.

War is the leading topic. The blowing up of the Maine is still unsettled.

Decades later, a textbook, The American Century, revealed the true motivations for the declaration of war against Spain. “On March 25, a close political advisor in New York cabled McKinley: ‘Big corporations here now believe we will have war. Believe all would welcome it as a relief to suspense.’”

In early April of 1898, President McKinley succumbed to such pressure with a war message. Meanwhile, in Seneca, Kansas, Mary Sly responds with suspicion about the political motivations of the President, as evidenced by her April 12th journal entry:

McKinley’s war message handed to Congress. Another subterfuge to screen “Gold Bugs.”

About a week later, we were at war with Spain to protect corporate interests. Mary Sly followed the news of the war with a surprising interest for one so far removed from the conflict. In her journal she notes the most significant details of the Spanish-American War.

April 21. No war yet. Spain rejects all propositions and our fleet is now for Cuban waters.

April 23. I hear the Nashville has captured a Spanish merchantman with supplies. The First Skirmish.

April 30. Dewey met and conquered the Spanish Fleet off Manila.

Now the war is in full swing. The U.S. achieves victory after victory in this “splendid little war,” and the U.S. military is seeking more and more soldiers. The war finally touches Seneca, Kansas, as Mary tells in the May 3, 1898 entry in her journal:

Recruiting officer is to be here in Seneca tomorrow. The war is in full blast.

The war continued, but Mary Sly never failed to see through the ploys of pomp and patriotism offered by the establishment, as her June 4, 1898 journal entry shows:

“Dewey Day.” I suppose all have tried to feel patriotic. I feel more like weeping than rejoicing. The brave and great are being

sacrificed to the merciless demands of greed and tyranny.

About three months later, the war was over and the soldiers were coming home. Mary was so relieved by their return that she enjoyed a good night’s sleep.

September 14. The soldier boys came in on the 10:00 train last night. They were given a loud reception but I slept through it all.

Mary Hammond Sly died on July 14, 1907, after a long eventful life. Although she died long before my birth, she speaks to me through her writings that were faithfully preserved by Ruth Sly Moriarty, my great-grandmother, and Ruth Moriarty Henry, my grandmother.

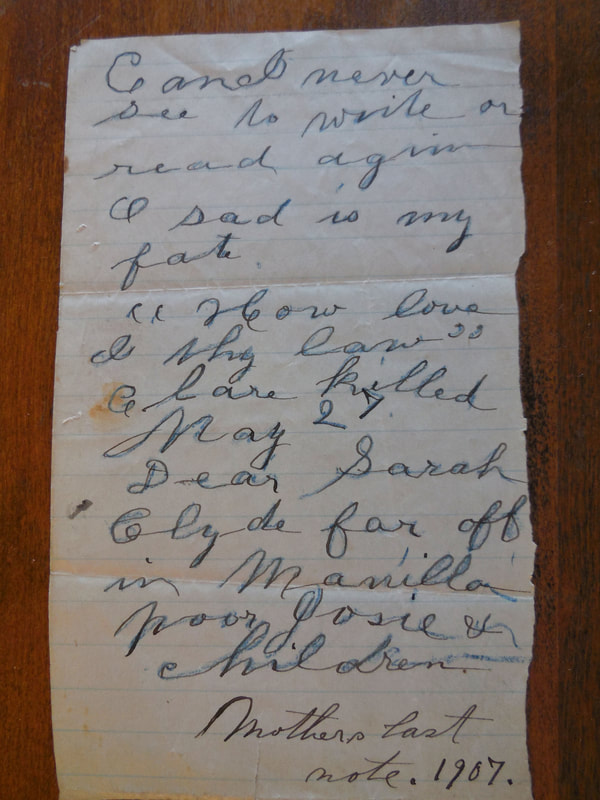

Among these writings in my possession is Mary Sly’s last note, the barely legible scrawl of a woman almost blind:

She abandoned spinsterhood in 1850 to marry John Sly, a farmer and abolitionist four years her junior, from Erie County, New York. The Slys farmed in Erie County for five years, then moved to Delaware County, Iowa. In the spring of 1857, they packed all their belongings and their young children, Cornelia and Philo, into an ox-drawn covered wagon and headed west to Kansas Territory where they sought land and breathing space.

In later life, Mary Sly — always politically active — became involved with Woman Suffrage and Populism. But throughout her long life, without neglecting family responsibilities and church and political activities, Mary found time to draw and paint and was diligent in keeping a written record of her thoughts and reactions to the history occurring around her. The words of Mary Sly, existing today in her letters and journal (the only one to survive my great-aunt’s deliberate fiery destruction), relate her character and give us an accurate history of the time.

John and Mary Sly, Nemaha County’s second and third settlers, established a home on Turkey Creek, near the present town of Seneca. During the half-century they lived there, they endured illness, deaths of loved ones, two wars — one close at hand and one distant — and political upheaval.

Wagon trains usually started the trek westward in the spring to avoid the intense cold and bad weather of fall and winter. The trip was especially difficult for Mary for a reason apparent in a letter dated November 22, 1857, which she wrote to her sister Elizabeth back East after the Slys were settled in Kansas. The family would have delayed the journey, she wrote, had she realized she had “started to Boston,” a pioneer’s polite euphemism for pregnancy.

You asked me to write more particularly concerning our journey. I was brief at that time on purpose, and, now shall be obliged to be, for want of time. However you shall have a short history of myself and if it goes to Washington through miscarriage so be it. Well then I did not dream I had “started to Boston” when we made calculations on coming to Kansas or we should not have come this year, but I was three months and over on the route and of course nothing was enjoyed by me. I felt sometimes as if I was going to my long home.

Cornelia and Philo were both very sick part of the time. We camped in our wagon mostly rain or shine, but had some good company the last three weeks. Were over five weeks coming. I have not to add that my lot was case in a goodly place and among good Christian people, and although I have suffered for the want of help to do my work, the neighbors have done all in their power.

An unpleasant initiation to the prairie were cases of malaria (ague) which pioneers often contracted when first out West. While suffering from malaria, Mary Sly gave birth to her third child, a task by no means easy while in good health.

We have all every one had the ague and fever and all down at once but Augustus, he waited till John was getting so that he

could make out to milk if the cow came up of her own accord. My ague came on every other day about 6 o’clock and sometimes I could help about the dinner and again not. I had the fever enough to burn me up almost.

Had it broke with calomel and quinine firstly but came down with it twice later and then employed a botanical Physician, who lives four miles from us in Nebraska, he gave 16 pills to be taken in 8 hours and I have not had but one shake since and that was the next day after my little Catharine Elizabeth was born. A good old lady was obliged to officiate as M.D. as the doctor had just gone, thinking I could wait until in the night. (I was glad he left though.) We could not get but two women and neither of them has a child in the world or ever had, others soon came but too late.

On September 17, 1858, Cornelia, Mary Sly’s oldest child, died of an undetermined ailment. Her death broke my great-great-grandmother’s heart.

Little did I think when I wrote you last that I should so soon have to take my pen again to communicate the sad tidings I do at this time. Yes, my dear Sister, your little favorite is no more. Cornelia, my own sweet darling Cornelia, is I have no doubt praising God in Heaven. She was taken last Thursday, Sept. 16, and died at sunrise the next morning.

She went into a fit about two o’clock and never came to, so as to sense anything to all appearances . . . . But Oh Elizabeth, the look, the last sad parting look she gave me, how can I describe it? I cannot, no I cannot. When I think of it I can scarcely keep from bursting right out crying.

Years later, Mary Sly still wrote of Cornelia in her journal, always with pitiful backward glances. A long poem entitled “Cornelia” — the last stanza of which follows — is especially heartrending.

To God I’ll go with every care,

And humbly seek in earnest prayer

For grace, that we may meet thee there,

Cornelia.

Cornelia Maria Sly departed this life September 17, 1858, aged 6 years nearly. Had Cornelia lived, to-day would have been her 25th birthday.

Without formal declaration, the American Civil War began well before 1861. The war was actually being fought in the legislative branch of national government as early as 1858. One of the main issues at hand was whether Kansas would be a slave or free state. According to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, introduced by Stephen A. Douglas, the residents of Kansas would determine by popular vote whether Kansas would be a pro- or anti-slavery state.

However, in late 1857, pro-slavers submitted the Lecompton Constitution to the state legislature, recommending that Kansas be admitted as a slave state, in repudiation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as well as the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Acting Kansas Governor Frederick P. Stanton put the Lecompton Constitution to a popular vote and the Constitution was soundly defeated on January 4, 1858.

In response, Southern extremists in Congress, backed by President Buchanan, passed the English Bill on the 4th day of May, 1858, which stated that if Kansas was voted a free territory, Kansas residents would lose four million acres of public land grants (i.e., the homesteaders in these areas would have to buy their land) and Kansas would not be declared a state until it had a population of over 90,000.

Understandably, Kansas residents were upset, and Mary Sly exemplifies their feelings in a letter to Elizabeth dated May 8, 1858:

Everything seems to go off right since the rejection of the Lecompton Constitution, except for the fiendish revenge manifested by Buchanan’s late proclamation to sell all the surveyed lands in the territory. The people are forming mob laws for their protection — in some places, not here. James Buchanan, unless he repents, will die an unenviable death, unwept, unmourned, and perhaps unhung.

By December, 1861, the Civil War on the frontier was booming. The Kansas pioneers were themselves victims of war, being caught between the anti-slavery Jayhawkers and the pro-slavery forces. Though on opposite sides, these two groups used the same tactics of terror. In the following letter, Mary Sly describes a run of bad luck and then becomes philosophical about her troubles.

. . . Don’t we have the luck? I do not mind if we can keep our health, and the worse than rebels will leave us alone. The Jayhawkers are all around and we are expecting trouble from them as we have been threatened. I have a poor opinion of them, let them be on which side soever.

At this time, settlers in Kansas were fearful of a large scale attack from Missouri, as the pioneers would be defenseless against the ruffians who despised them. Again in the letter of December 8, 1861, Mary Sly characterizes the settlers’ fears.

We understand that North Missouri is all in rebellion again. We are afraid that as soon as the river freezes over they will step across into Kansas and make all the destruction possible. They hold such a deadly hatred to Kansas.

The huge-scale attack from Missouri did come, but not until 1864, when General Sterling Price and his rebels stabbed into Kansas. In another letter to Elizabeth, dated October 17, 1864, Mary Sly describes the situation.

At present the railroads are all in rebel hands in Missouri, or nearly so, Price in connection with others are playing Smash there . . . Every able bodied man is called off after Price. The present hour for Kansas is a critical one indeed. Indians on the south and west, and rebels on the east and both trying to do her all the injury they can, still I hope she will escape a general extermination.

When the Civil War ended, Mary Sly was in her early forties. Her liberal upbringing, coupled with the physical and economic hardships she endured on the frontier had served to forge her into an iron-hard individualist. Three decades later, Mary Sly used her journal to report with great candor on the social, political and personal events which affected her life in the 1890s.

One of the more serious aspects of life on the prairie was illness and its treatment. Mary Sly reports at length on medical topics, probably due to the fact that four of her eight brothers were doctors, all of whom lost their lives in the Civil War. Her remaining four brothers were dentists.

An acquaintance of Mary Sly, Emma Smith Williams, had breast cancer and was desperate to be healed of it. In April, 1898, Mary Sly wrote in her journal:

She that was Emma Smith is down from Beaty [Nebraska] to consult the doctors about a cancer on her left breast.

Evidently, Mrs. Williams’ prognosis was grim, for less than a week later, she desperately turned to a frontier healer, a charlatan of the type that sold alcohol-based cure-alls to those who hoped for better health. In a journal entry on April 10, 1898, Mary Sly confided her opinion of such “healers.”

Ruth [Mary Sly’s daughter] went with Emma Smith to Kansas City to see Carson the Magnetic Healer, but to no purpose. He is a humbug. Emma went home Thursday. I think the cancer incurable.

Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Williams, still seeking a cure, sought help from a cancer specialist. A July 23, 1898 entry states:

Ruth has just gone to the depot with Emma Williams who has been three months to Wichita doctoring for cancer with Dr. M. S. Rochelle, specialist.

At some point in her treatment, Mrs. Williams had what was then considered very radical and experimental surgery, a mastectomy. Science marches on in the Nineteenth Century, as noted on February 21, 1899.

Mrs. Emma Williams called as she is moving to Oklahoma. She showed me where her cancer was taken off, the left breast all gone.

Perhaps the pioneers’ greatest fear was that of an epidemic, as doctors were scarce and inoculations were rare or for some diseases uninvented. An epidemic of typhoid, smallpox, or diphtheria could strike with devastating results. In her journal, Mary chronicles one of the local smallpox scares.

Feb. 21, 1899. Smallpox in town. Dr. Troughton’s son.

Feb. 22, 1899. Dr. Troughton’s house is quarantined and he is like a caged lyon [sic]. Geo Williams’ folks have left their fine house for a time until the smallpox question is better understood.

Feb. 24, 1899. The authorities have built a Pest House and last night removed young Troughton to it.

Feb. 26, 1899. Conference [Methodist Church] is moved from Seneca on account of smallpox.

March 1, 1899. J. B. [Moriarty, husband of Mary Sly’s daughter Ruth] has just drove up with his new mule team. Their children vaccinated.

March 3, 1899. Young Troughton is still a smallpox patient. He is the only one that has it in town as yet.

March 4, 1899. Hear nothing from the “pest” House, nor of any additional cases. Hope no more have it. Old Mrs. Hale is

quarantined.

March 17, 1899. Mrs. Troughton’s sister in the Pest House, down with smallpox.

The entry on March 17th was the last one pertaining to the smallpox scare. Fortunately, the disease was confined to only a few people, including the local doctor’s son and sister-in-law.

The women’s liberation movement is not a recent one. Mary Sly, in her seventh decade, was extremely involved in the movement and her relatives knew it. On April 11, 1894, she noted in her journal that her brother had sent her an item of mutual interest.

W. W. Hammond sent me a Boston paper in which is a fragment of the welcoming speech to the Equal Suffrage Convention held in Boston last week. I am glad to learn he favors Woman Suffrage.

Mary Sly’s thorough involvement in the Suffrage movement occasionally caused friction with others who were less enthusiastic about it. Once such case occurred after Mary recorded that a church member came to her door on October 31, 1894,

soliciting a chicken pie towards feeding the people on election day,

Nov. 6th.

Before the election, however, a conflict developed between the preacher of the church and Mrs. Sly, about which she says:

If our preacher is too conscientious to vote for Woman Suffrage, the

church may furnish its own chicken pie.

In the 1890s, the United States suffered one of its worst depressions ever. It seemed that nothing could bring the country out of this intolerable slump. Vagabonds were omnipresent, especially in the Midwest, as Mary Sly testifies on May 26, 1894:

Seneca is down on the tramps.

Again, on July 13, 1895, she writes:

Just fed another tramp. The country is full of them. Grover [Cleveland] will get to his end after a while.

And a year later, she is still beset by beggars:

Decoration Day. A tramp to feed calls.

In a time of such poverty, one often becomes quite disillusioned with the whole political system, and Mrs. Sly is no exception. Her disgust is apparent in a November 3, 1894 entry:

Tonight a Democrat speaks at the Hall and the Suffragists at the Court House. They are all such liars I do not want to go.

The disillusionment of many agrarians like Mary Sly led to the formation of a strong new party, the Populists. Those in the Populist Party felt that the depression of the 1890s was due to the fact that the gold standard kept money in the hands of few, and when the gold supply became ever scarcer in the United States, these “goldbugs” would prosper while others starved.

Leading the Populists was a Nebraska gentleman named William Jennings Bryan who said at a speech in Chicago in 1896:

There are two ideas in government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up through every class and rest upon us.

Thus, the Populists wanted a silver and gold standard to place more money in the hands of the less prosperous, namely the farmers.

On November 6, 1896, the Populists’ presidential candidate, W. J. Bryan (a Democrat), squared off against the Republican “goldbug” William McKinley. As did many other farmers, the Slys threw their support to Bryan. The Populists’ dreams were not to be fulfilled in 1896, however, because as Mary reports in her journal on November 11,

Election has resulted in the defeat of Bryan the Free Coinage Candidate, of both gold and silver at 16 to 1, that is 16 oz of

silver = in value 1 oz of gold. McKinley carried 23 states, Bryan 21. Delaware and Kentucky doubtful yet.

Mary Sly’s hopes for free coinage did not end with McKinley’s election, because in January of 1897, she writes:

The year comes in “like a lamb.” I hope it may prove a peaceful and happy year to us nationally. McKinley will soon occupy the presidential chair and if Congress will give the people more money, there will no doubt be greater prosperity.

Without doubt, McKinley’s victory over Bryan upset Mrs. Sly a great deal for she notes on March 4, 1897 that:

Wm McKinley inaugurated to-day. A dull, gloomy day in keeping with the times.

In the late Nineteenth Century, as now, officials in the church felt no trepidation about expressing their political ideas from the pulpit. In 1897, a visiting official from the Methodist Church gave a lecture which greatly angered Mary.

McKabe lectured here the 13th. He is a “gold bug.” I have no use for such bishops!

Meanwhile, Bryan, the free coinage advocate, was still very popular, as Mary tells us on October 4, 1897:

Received and answered Brother William’s invitation to come and hear Bryan speak in Kansas City. Our health will not permit us to go.

She adds on October 7th that,

Bryan’s speech was successful. 15,000 paid $.25.

Mr. Bryan was obviously to remain in the limelight.

In late January, 1898, the U.S. warship Maine was sent to Havana, Cuba, to protect U.S. interests. Only two weeks later, on February 15, 1898, the ship blew up under mysterious circumstances, resulting in the deaths of over 250 American sailors. Mary Sly noted the major event and the controversy surrounding it on March 14th.

War is the leading topic. The blowing up of the Maine is still unsettled.

Decades later, a textbook, The American Century, revealed the true motivations for the declaration of war against Spain. “On March 25, a close political advisor in New York cabled McKinley: ‘Big corporations here now believe we will have war. Believe all would welcome it as a relief to suspense.’”

In early April of 1898, President McKinley succumbed to such pressure with a war message. Meanwhile, in Seneca, Kansas, Mary Sly responds with suspicion about the political motivations of the President, as evidenced by her April 12th journal entry:

McKinley’s war message handed to Congress. Another subterfuge to screen “Gold Bugs.”

About a week later, we were at war with Spain to protect corporate interests. Mary Sly followed the news of the war with a surprising interest for one so far removed from the conflict. In her journal she notes the most significant details of the Spanish-American War.

April 21. No war yet. Spain rejects all propositions and our fleet is now for Cuban waters.

April 23. I hear the Nashville has captured a Spanish merchantman with supplies. The First Skirmish.

April 30. Dewey met and conquered the Spanish Fleet off Manila.

Now the war is in full swing. The U.S. achieves victory after victory in this “splendid little war,” and the U.S. military is seeking more and more soldiers. The war finally touches Seneca, Kansas, as Mary tells in the May 3, 1898 entry in her journal:

Recruiting officer is to be here in Seneca tomorrow. The war is in full blast.

The war continued, but Mary Sly never failed to see through the ploys of pomp and patriotism offered by the establishment, as her June 4, 1898 journal entry shows:

“Dewey Day.” I suppose all have tried to feel patriotic. I feel more like weeping than rejoicing. The brave and great are being

sacrificed to the merciless demands of greed and tyranny.

About three months later, the war was over and the soldiers were coming home. Mary was so relieved by their return that she enjoyed a good night’s sleep.

September 14. The soldier boys came in on the 10:00 train last night. They were given a loud reception but I slept through it all.

Mary Hammond Sly died on July 14, 1907, after a long eventful life. Although she died long before my birth, she speaks to me through her writings that were faithfully preserved by Ruth Sly Moriarty, my great-grandmother, and Ruth Moriarty Henry, my grandmother.

Among these writings in my possession is Mary Sly’s last note, the barely legible scrawl of a woman almost blind:

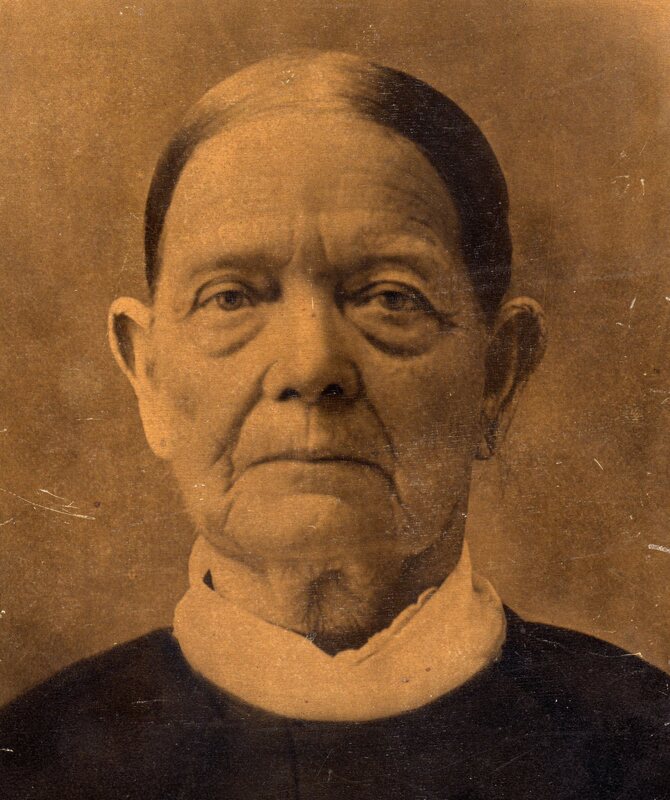

This oil painting was done by Mary Hammond Sly. In the right hand corner is her name and the date it was painted: 1870. The Civil War had been over for five years and I believe this may have been her home on Turkey Creek in Nemaha County, Kansas. I bought this painting at my grandmother Ruth Moriarty Henry's auction in 1978 for $70, a price that stunned me and my husband Ray who offered to hold his hand over my mouth if I would hold his hand down, a reference to the many bids he had won in an attempt to raise the bids, not actually buy the items.